This blog was originally written for and published on the SparkFun Electronics site.

For a long time I was a believer that art and engineering were two separate, basically opposite, things. Art is all feeling, weird, subjective, right brain-y. Engineering is logical, 1’s and 0’s, quantitative, left brain-y. As someone who is an engineer and artist, I always thought I existed as those two things individually. This was until I started working with Trey Duvall.

ColumnRopeColumn, 2020 - photos courtesy of the artist

Trey is an artist working in Denver. He teaches at the Rocky Mountain College of Art and Design and is the founder of SITE Gallery in Houston. His work is highly conceptual and therefore takes on many different forms from what could be considered more traditional ‘sculpture’ to large-scale installation, video, performance, and other sculptural and organizational mediums. Trey’s work focuses on relationships between agency and absurdity, permanence and failure, and the material language of functioning forms. Entropy, futility, humor, duration, stamina, and material or physical exhaustion are central underpinnings to his work.

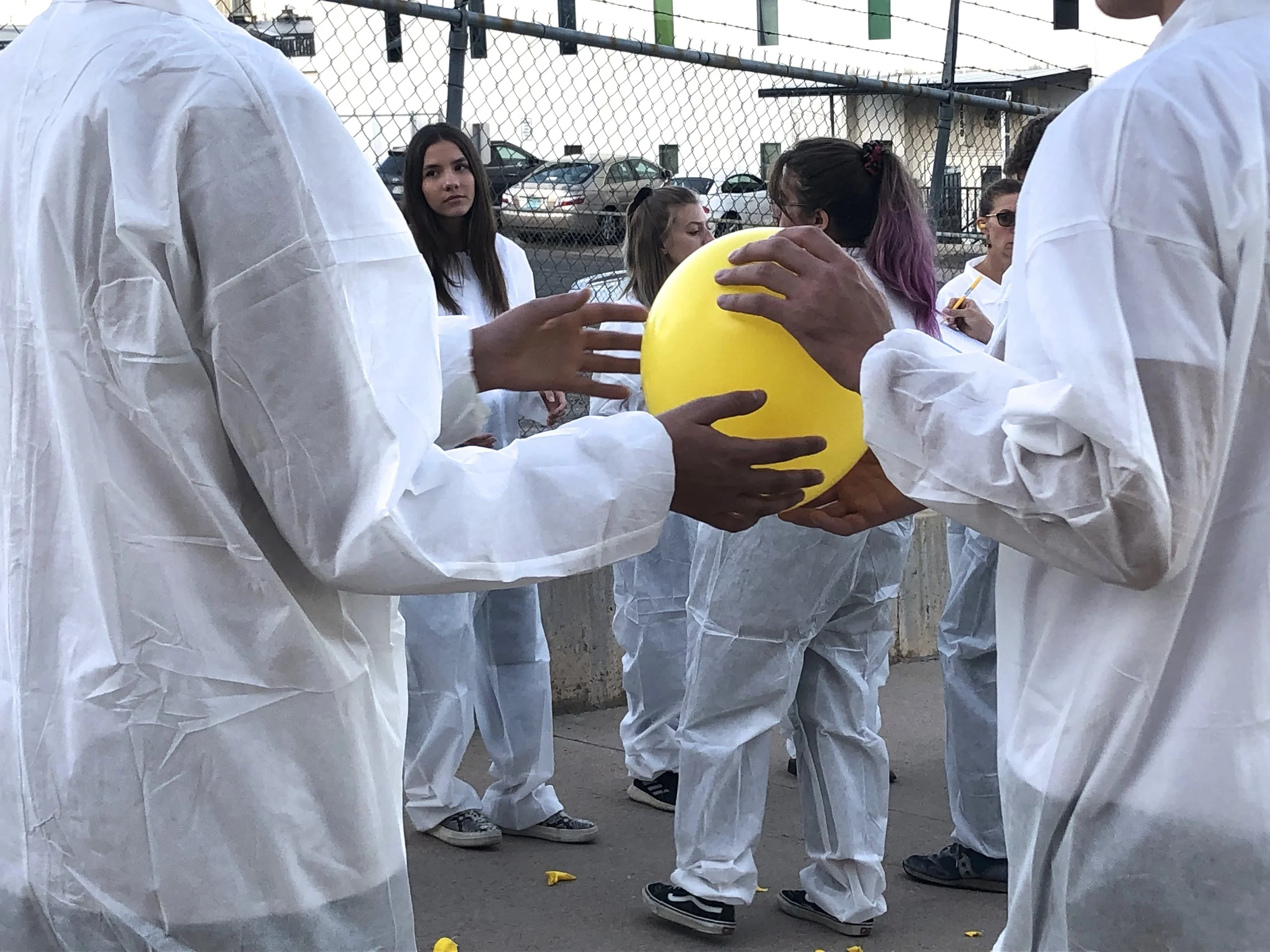

For the last two years I’ve been Trey’s intern, studio assistant, and most recently his “technical advisor,” which is a position we jokingly made up because the ambiguity of what we need to do in the studio resists any attempt at a single title. A job that started as meticulously hand-sanding acrylic and taking detailed measurements of hundreds of inflated yellow balloons has become an opportunity to flex my engineering muscles as his art moves further into kinetics and dynamic systems to create functioning examples of dysfunction and absurdity.

WorkFlow002, 2019 - That’s me with the purple ponytail!

Trey, how do you use engineering as a vehicle to convey a concept? What does the automation of movement add to your pieces?

“A lot of my work deals with repetition, doing the same task over and over until the point of exhaustion or failure. I think of the kinetic systems as performative objects, designed to demonstrate ongoing cycles or work that is seeming undoing rather than doing. The work is ongoing, you can come and go and the work is still there and running, on loop, doing the same thing, or nearly the same thing as when you left it. There is a fine line that these pieces need to walk between functionality and perceived failure, or between effort and perceived failure. Sometimes the work actually fails, systems that are designed to run until failure, and the point of failure ends up being what is shown. However, I am often looking for a system that can reliably perform while appearing to be ready to fail at any time, or perform in a way that conveys struggle or misuse, misalignment.

Designing failure, or designing unpredictability is the task that is driven by the concepts of my work. Designing motion or behavior that will predictably act in unexpected ways, or reliably operate in unexpected ways, or create unspecified results is how engineering challenges my work. The automated movement helps demonstrate the act of undoing, or create unexpected results from seemingly simple and fixed variables. When a person see these systems, or tool, some object that you expect to work a certain way, or is readily relatable or understandable, and then that thing behaves in a way that is unexpected or seemingly unintended, functions in a way it is not supposed to, the underlying fragility of of other behaviors, systems, expectancy and familiarity can also be easily questioned.”

These are the pieces I’ve seen come to life:

Spool/Unspool, 2019

Fort Lewis College, 2019 - photos by Mariah Richstone

Fort Lewis College, 2019 - photos by Mariah Richstone

Spool/Unspool is an evolving site-specific sculpture that delivers 36 thousand feet of rope onto the gallery floor over the duration of the exhibition. Spool/Unspool runs continuously, creating a slow transfer from the organized state of the rope on spools to a circumstantial and purposeless heap.

Spool/Unspool was first shown at the University of Wyoming Art Museum as a part of Do, Do, Do, Do, Do and again at Fort Lewis College as a part of Hat On A Hat.

Latent Variability in Axiomatic Structures, 2020

This work explores the potential for chance and uncontrollability within fixed structures and set values. Unexpected compositions and behaviors exist within simple arrangements, and potential future states of change cannot be assumed or predicted. 1+1= 1,000,000. Shifting starting conditions creates the subtle potential for near limitless orientations of forms in space and compositions of sound from sequence to sequence.

Latent Variability in Axiomatic Structures was shown at RedLine Contemporary Art Center.

Lift/Fall, 2020

One By One, 2020 - photos by Wes Magyar

Part of One by One, a group exhibition at RULE Gallery's Denver location, Lift/Fall continuously raises and drops a 60’ loop of yellow polypropylene rope using a cast plastic drive wheel.

Curtain Lift/Curtain Drop, 2020

Entirely Devoid, 2020 - photos by Wes Magyar

Entirely Devoid, 2020 - photos by Wes Magyar

Curtain Lift/Curtain Drop, operates within a system that is contentious. As the curtain labors upward, the anticipation of reaching the top rises in the viewer, culminating in a stagnant curtain. This implied stability is ultimately withdrawn as the curtain falls and the process begins again, becoming both untenable and unsustainable.

The Denver Post reviews Trey’s show Entirely Devoid here.

Process

Once Trey comes up with an idea he works on the mechanical design and I design the circuitry and write the code. I’d be lying if I said being a SparkFun engineer didn't give me a significant advantage to designing these electrical systems. As we know, SparkFun Electronics caters to the inventor at home, so of course I’m biased to our products. Here are the products we most generally use:

https://www.sparkfun.com/products/15123

https://www.sparkfun.com/products/15451

https://www.sparkfun.com/products/retired/12262

https://www.sparkfun.com/products/15664

Though the mechanics and movement of these pieces might seem really similar, the system design is tailored to the individual piece and the concept it conveys. Our system has been evolving and improving from one piece to the next. Speed, movement, material, sound, and overall experience are intentional to Trey’s art and therefore lends itself to nuance in the design. No two art pieces are the same.

As a rookie engineer, my work with Trey has definitely put my engineering textbook knowledge into practice. I’m constantly learning new things and building up my self-confidence as an engineer and artist. Probably the most challenging part of this work has been sourcing the correct motor. DC, AC, stepper, servo, gear, brushless, brushed: there are so many types of motors! I’ve also had to dust off my physics kinematic equations to calculate torque. Turns out you need a lot more torque than you might think to lift or move things. These systems also require a lot of stress testing and need to be easy to use. They get installed in galleries where they operate during business hours (often eight hours at a time) and are handled by curators or preparators who have differing levels of comfort with the systems. What is installed in the gallery needs to be simple to operate, more or less flip on and flip off. Generally, timing is key to a Trey art piece so that takes some coding finesse. And the most recent engineering feat we conquered is the free fall (as seen on Curtain Lift/Curtain Drop), but I will keep the details of how we did that close to the chest, but believe me, it is really fancy.

Curtain Lift/Curtain Drop - here’s a little video I got when testing free fall in the studio

What’s next in the studio? Trey and I are currently working on several new pieces and we’re branching out to use stepper motors. We are also in the process of helping Jaime Carrejo with a few pieces for his upcoming show at the Museum of Contemporary art in Denver. Stay tuned!